The historical context: from biological necessity to ethical scrutiny

Animal experimentation has underpinned science for centuries: biomedical research and toxicology relied on animals to probe physiology, create therapies, and assess the safety of chemicals and medicines. The choice had a practical foundation, since animal models were, for a long time, the only living systems capable of reflecting whole-organism complexity, including integrated organ crosstalk, metabolism, and an intact immune response. From Galen’s first observations to the twentieth-century breakthroughs behind vaccines and insulin, animal models have made undeniable contributions to human health.

A history of dependence: why animals were used

The human body is a complex system. Evaluating a new drug is not just about whether a compound harms cells in a Petri dish, but also how it is absorbed, how it is distributed through the bloodstream, how the liver metabolizes it, and how the kidneys clear it. Historically, only animal models offered that integrated, systemic view.

As science advanced, the scale of animal use grew, and so did ethical concern. It helps to be clear about that starting point before discussing replacement. In the European Union, the number of animals used in scientific procedures remains substantial, with millions recorded annually. In Spain, the mouse (Mus musculus) is still the most frequently used species, showing that a large portion of basic and applied research continues to depend on these models. The volumes involved, both in research and in education, justify the urgency of applying the 3Rs with rigor and investing in advanced alternatives.

The scientific crossroads: when animal models fall short

Animal use is not only an ethical issue; it also has scientific limitations. Chief among them is the problem of inter‑species extrapolation. Although humans share evolutionary ancestry with many laboratory species, differences in genetics, metabolism, and physiology are large enough to skew results.

That predictive gap has real‑world impact. If a candidate drug fails to show efficacy or looks toxic in animals, it is often abandoned too soon. Promising compounds that could be effective and safe in humans may never be developed. A well‑known case is Pfizer’s atorvastatin (Lipitor): early animal testing did not look encouraging, whereas a small trial in human volunteers proved successful and the drug went on to become a widely used cholesterol‑lowering therapy.

These examples shift the debate. The case for change is no longer purely ethical, it is also scientific and economic. Alternatives that are intrinsically more relevant to human biology, such as 3D models or organ‑on‑a‑chip systems, are not only more humane; they offer a better way to reduce the risk of costly, late‑stage clinical failures. In short, science itself is asking for better models.

The ethical and regulatory framework: the 3Rs paradigm

Recognition of those scientific limits, together with growing ethical unease during the twentieth century, set the stage for regulatory reform. In 1959, William M. S. Russell and Rex L. Burch published The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique, laying out what became the global standard: the 3Rs.

Russell and Burch’s foundation

The 3Rs set a practical bar for minimizing animal use and maximizing welfare in laboratory research. They are not just moral guidelines; they have been written into law worldwide and now act as a concrete roadmap for modern science.

- Replacement: the ultimate goal. Use non‑animal alternatives whenever possible. Replacement may be total (no animals at all) or partial (e.g., substituting vertebrates with invertebrates or embryos). AI and advanced in vitro models clearly sit in this category.

- Reduction: use the smallest number of animals needed to obtain statistically robust results. Achieve this through better experimental design, stronger statistics, and high‑throughput methods that extract more information per subject.

- Refinement: modify procedures, care protocols, and study designs to minimize pain, distress, or suffering in any animals that are still used.

Europe’s regulatory response: global leadership

The European Union has been a pioneer in adopting and enforcing the 3Rs. The most visible milestone under Replacement was the full EU ban on animal testing for cosmetics, proving that a large, highly regulated industry can operate under a complete replacement principle.

In research, Directive 2010/63/EU governs animal use for scientific purposes, turning the 3Rs from ethical guidance into legal mandate. Large regulatory frameworks such as REACH (Registration, Evaluation, Authorisation and Restriction of Chemicals) have also driven the development and validation of alternatives at scale. The challenge of testing thousands of chemicals under REACH created a strong regulatory pull to invest in replacement technologies.

Infrastructure for validation and transparency

Acknowledging the 3Rs is not enough; dedicated institutions are needed to validate and deploy the principles. These bodies turn intent into scientific policy.

In Europe, the European Union Reference Laboratory for alternatives to animal testing (EURL ECVAM) plays a central role by coordinating the validation and dissemination of alternative methods. Validation is the bottleneck that turns a promising lab technique into an internationally accepted regulatory standard. It ensures an alternative is at least as reliable and predictive, ideally more so, than the animal assay it seeks to replace.

In Spain, national promotion of the 3Rs is accompanied by strong transparency initiatives. The COSCE Transparency Agreement commits scientific institutions to communicate clearly about their animal research, disclosing when a discovery relied on animal work and, crucially, reporting how each institution applies the 3Rs with concrete examples of progress. Active transparency, including publication of the numbers and species used, builds public trust and accelerates ethical compliance.

SECAL, the Spanish Society for Laboratory Animal Science, places particular emphasis on Refinement by improving standards of care and fostering cooperation among institutions.

By institutionalizing validation (EURL ECVAM), transparency (COSCE), and welfare improvement (SECAL), Europe has built the scaffolding required for rigorous, science‑led adoption of new technologies.

The new biology: high‑fidelity in vitro and ex vivo models (NAMs)

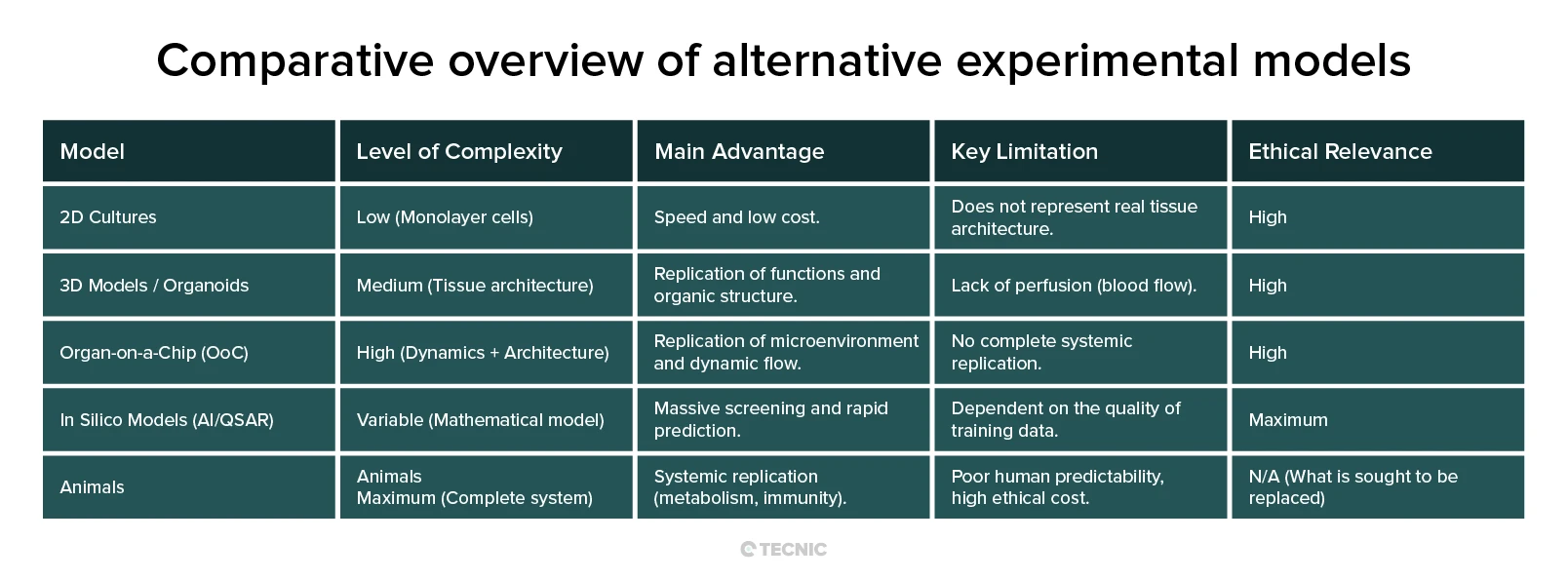

The main engine of Replacement is the development of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs), both biological and computational. These models aim to replicate human biology much more faithfully than traditional animal models.

Beyond the Petri dish: the leap to 3D

For decades, in vitro research relied on 2D cell culture, where cells grow flat on plastic. It is fast and inexpensive but fails to reproduce the true microenvironment of the body. In vivo, cells are embedded in a 3D matrix, interact with neighbors in multiple planes, and experience gradients of nutrients and oxygen.

The breakthrough came with 3D models such as spheroids and organoids. Organoids self‑organize to replicate the architecture and function of specific tissues, gut, liver, brain, among others. They enable the study of complex diseases, including cancer and developmental disorders, in a context far more relevant to human physiology than a simple monolayer culture.

Microphysiological systems: organ‑on‑a‑chip (OoC)

If organoids capture 3D architecture, organ‑on‑a‑chip adds dynamic function. OoC devices are micro‑engineered systems, typically no larger than a USB stick, with tiny channels lined with living human cells and tissues. Continuous perfusion mimics blood flow and exposes cells to a microenvironment much closer to real life.

Key advantages include:

- Human relevance: use of human cells, often patient‑derived, eliminates the inter‑species extrapolation problem.

- Precise control: variables that are impossible to isolate in an animal can be controlled, for example, mechanical forces like stretch and compression in the lung, or finely tuned chemical gradients.

- High‑throughput screening: the small footprint and inherent automation make them ideal for testing large numbers of compounds.

The logical next step beyond a single‑organ chip is the “body‑on‑a‑chip,” which connects multiple chips (e.g., liver, kidney, brain) through fluidic channels to recreate systemic interactions and drug metabolism. This approach tackles the last limitation of in vitro models, the lack of whole‑body complexity, while preserving the advantages of human biology.

Alternative organisms and other biological NAMs

Replacement does not always mean purely acellular systems. In many cases, alternative organisms with simpler biology or a different ethical status are preferable to higher vertebrates.

Non‑vertebrate models such as Drosophila melanogaster and Caenorhabditis elegans have long been used in basic research on development and genetics. Their use now extends to high‑throughput chemical and drug screening because they allow parallel testing and automated analysis at scale.

Other useful systems include early embryos of zebrafish or chicken. Although they are vertebrates, their earliest developmental stages are not considered “experimental animals” under EU law and can serve as efficient screening tools.

The revolution in NAMs marks a fundamental pivot. Traditional animal models were adopted for their systemic complexity. Modern in vitro systems, organoids and OoC, do not try to mimic an animal; they target specific human functions. By focusing on human physiology (flow, pressure, cell‑cell interactions), these technologies yield models that are often more predictive for humans than in vivo models from another species.

Artificial intelligence: in silico replacement and predictive toxicology

AI and in silico modeling form the frontier of Replacement, making it possible to predict outcomes and run screens before any physical experiment is carried out.

Predictive modeling basics

Predictive modeling is not new. Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models have long estimated the toxicity of molecules from their physical and chemical properties (molecular descriptors). QSARs have been foundational in environmental toxicology and chemical safety.

The real leap came with modern machine learning and deep learning. These algorithms detect complex patterns in massive datasets at speeds and accuracies beyond traditional statistics. They can now predict not only basic toxicity but also the likely metabolic fate of a substance.

AI in early discovery and toxicology

AI is transforming early‑stage research. In drug design, it can propose thousands of candidate molecules and, crucially, rank their expected efficacy and toxicity before any synthesis or biological test. That accelerates discovery and optimizes resources.

The clearest ethical benefit is a direct reduction in animal use. With predictive screening, compounds that are likely to be toxic in humans can be rejected virtually, avoiding costly and ethically sensitive wet‑lab steps. AI thus provides an ethical alternative that respects animal welfare.

AI is most powerful when combined with biological NAMs. High‑throughput experiments in organoids and organ‑on‑a‑chip generate huge, complex datasets. AI is essential to manage and interpret them, uncovering toxicity signatures and mechanistic patterns that would otherwise be hard to detect.

The reality: potential versus full replacement

AI is advancing rapidly and will change the life sciences. For now, animal models still play a role in certain contexts. AI has the potential to end animal research, but it has not yet achieved complete replacement.

The limiting factor is not the algorithm; it is the data. If AI is trained mainly on animal‑derived datasets, which are often poor predictors of human outcomes, the models will inherit those biases. The true in silico revolution will come as AI is trained predominantly on high‑fidelity human data produced by rigorously validated NAMs, for example, OoC platforms.

Seen this way, AI is the connector of the new biology. It does not replace the animal directly; it replaces the need to run vast numbers of physical experiments. AI becomes a predictive bridge between molecular structure and human biology, helping to validate hypotheses virtually. The synergy between biological “hardware” (OoC producing human data) and AI “software” (analyzing and predicting) is what can accelerate and ultimately secure full replacement.

Remaining challenges and what’s next

Despite strong progress in NAMs and AI, the goal of “zero animals” still faces significant regulatory and biological hurdles.

Regulatory validation

The largest barrier to widespread adoption is regulatory validation. To replace an entrenched animal assay, a new method must show, through rigorous, multi‑site studies, that it is at least as robust, reproducible, and predictive (ideally better). In Europe, EURL ECVAM coordinates this process.

Validation is long and expensive, and acceptance in the EU must be mirrored by other authorities (e.g., the FDA in the United States or agencies in Asia) before a method can become a universal industry standard.

Recreating immune and brain interactions

Although OoC platforms are excellent for modeling isolated organ function, recreating systemic crosstalk and the complexity of certain biological systems remains hard.

The immune system is one of the biggest challenges. Its vast network of cells and signals responding to infection, inflammation, and autoimmunity is difficult to reproduce in vitro with full fidelity. Body‑on‑a‑chip approaches are working to integrate immune components, but the task is complex.

Another hurdle is chronic and repeat‑dose toxicology. Long‑term effects, carcinogenesis, months‑long drug accumulation and metabolism, remain difficult to simulate in short‑lived in vitro models.

Here lies a paradox. Systemic complexity is often the last argument for animal use, yet history shows animal models can be poor predictors of human response. The objective should not be to recreate an animal; it should be to invest in technology that builds human complexity through interconnected systems like body‑on‑a‑chip. The limitation is less about technology and more about letting go of a paradigm with low human predictivity.

Ethics and public perception

Transparency is essential. Spain’s COSCE Transparency Agreement, which requires institutions to report their application of the 3Rs and to publish details of animal use, is key for public trust. Industry groups such as AseBio also support transparency, acknowledging the historical role of animal research while highlighting the intense effort to find alternatives. This public commitment to Refinement and Replacement helps ensure that the transition proceeds with ethical responsibility.

Conclusions

The history of animal experimentation reflects a time when there was no better option. The future is shaped by the convergence of ethical duty and the scientific superiority of New Approach Methodologies.

Summary of the technological convergence

Today’s biomedical revolution sits at the intersection of information technologies and micro‑engineering. Advances in cell biology have enabled organoids and 3D cultures with realistic tissue structure. Engineering has delivered organ‑on‑a‑chip platforms that recreate human microenvironments. Artificial intelligence then acts as the predictive engine that processes high‑fidelity data from these NAMs, accelerating discovery and enabling virtual toxicology, in silico replacement.

EU legislation, from the cosmetics testing ban to Directive 2010/63/EU, together with validation bodies such as EURL ECVAM and national transparency initiatives like COSCE, provides the institutional backbone that turns technological progress into mandated practice.

Ethics and public perception

The ultimate goal is human‑centric science. By using models built from human cells, discovery becomes more relevant and more predictive, reducing the high failure rates caused by inter‑species extrapolation.

In the end, replacing animals is not only about ethics; it is about better science. As body‑on‑a‑chip platforms and AI mature, they will be able to recreate human systemic complexity more accurately than conventional animal models.

Frequently asked questions (FAQ) on animal experimentation and AI

NAMs are modern, non-animal approaches that include in vitro systems (2D cultures, organoids), microphysiological systems such as organ-on-a-chip, and in silico tools like AI and QSAR. They aim to deliver human-relevant evidence while reducing or replacing animal use.

Organoids are 3D self-organized tissues that replicate organ architecture and selected functions. Organ-on-a-chip adds controlled microfluidic flow and mechanical cues, creating a dynamic, perfused microenvironment closer to in vivo conditions.

It connects multiple organ chips (for example, liver, kidney, brain) through fluidic channels to simulate systemic crosstalk and metabolism. This helps capture whole-body interactions without using an animal model.

Replacement (use alternatives to animals), Reduction (use the fewest animals needed for robust results), and Refinement (minimize pain and distress when animals are still used). They guide ethical and regulatory practice across the EU and beyond.

AI enables predictive toxicology and virtual screening, ranking compounds by likely efficacy and safety before synthesis or wet-lab testing. When combined with high-fidelity data from organoids and OoC, AI helps prioritize human-relevant candidates and avoid unnecessary animal studies.

Not yet. The main constraint is data quality. If models are trained on animal-derived datasets, their predictions inherit those biases. Full replacement depends on training AI with rigorous human data generated by validated NAMs.

Directive 2010/63/EU governs the use of animals for scientific purposes, embedding the 3Rs in law. REACH drives large-scale safety assessment of chemicals and has accelerated the development and validation of alternatives.

The European Union Reference Laboratory for alternatives to animal testing coordinates the scientific validation of alternative methods. Validation demonstrates that a NAM is at least as reliable and predictive as the animal assay it replaces, enabling regulatory acceptance.

COSCE promotes transparency about animal use and application of the 3Rs. SECAL focuses on best practices in care and use, emphasizing Refinement. Together they support responsible, open science and the adoption of alternatives.

In many contexts, yes. Human-cell models focus on human biology, which avoids inter-species extrapolation. While no single model fits every question, organoids and OoC often provide more directly human-relevant evidence.

Complex immune interactions, brain circuitry, and long-term or repeat-dose toxicology remain challenging to model. Body-on-a-chip is advancing these areas, but further validation and data are needed.

Quantitative structure–activity relationships use molecular descriptors to predict biological activity or toxicity from chemical structure. QSAR is a cornerstone of in silico assessment and complements AI approaches.

Typically yes. AI-guided triage and high-throughput NAMs focus resources on the most promising candidates earlier, reducing late-stage failures and shortening development cycles.

Match the model to the question. Use organoids for tissue-level biology, OoC for dynamic microenvironments and mechanobiology, AI/QSAR for virtual triage, and consider animals only where systemic complexity cannot yet be replicated with human-relevant NAMs.

References

- European Parliament, & Council of the European Union. (2010). Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes. EUR-Lex.

- European Commission. (n.d.). Ban on animal testing (cosmetics). Single Market & Industry.

- European Commission, Joint Research Centre. (n.d.). EU Reference Laboratory for alternatives to animal testing (EURL ECVAM).

- European Chemicals Agency (ECHA). (n.d.). Understanding REACH.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2024). (Q)SAR Assessment Framework: Guidance for the regulatory assessment of (quantitative) structure–activity relationship models and predictions (2nd ed.).

- OECD. (n.d.). OECD QSAR Toolbox.

- Vamathevan, J., Clark, D., Czodrowski, P., et al. (2019). Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, 18(6), 463–477.

- Zhang, B., Radisic, M., & Riahi, R. (2018). Advances in organ-on-a-chip engineering. Nature Reviews Materials, 3, 257–278.

- Leung, C. M., de Haan, P., Ronaldson-Bouchard, K., et al. (2022). A guide to the organ-on-a-chip. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 2, 33.

- Kim, J., Koo, B.-K., & Knoblich, J. A. (2020). Human organoids: Model systems for human biology and medicine. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 21(10), 571–584.

- National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). (n.d.). Tissue Chip for Drug Screening.

- U.S. Congress. (2022). FDA Modernization Act 2.0 (S.5002). Congress.gov.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2025, April 10). Roadmap to reducing animal testing in preclinical safety studies.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (2025, July 31). Implementing alternative methods.

- Confederación de Sociedades Científicas de España (COSCE). (2023, December 5). Presentación del sexto informe anual del Acuerdo COSCE por la transparencia en experimentación animal.

Key takeaways

- AI plus NAMs such as organoids and organ-on-a-chip reduce reliance on animal experimentation and increase human relevance.

- Regulatory anchors include the 3Rs, Directive 2010/63/EU, validation through EURL ECVAM, and REACH.

- Best current uses are predictive toxicology, early virtual screening, and mechanistic insights with human cells.

- Main gaps involve immune system integration, brain circuitry, and long term or repeat dose toxicology.

- The path forward is more high quality human data to train AI plus multi organ body on a chip for systemic effects.

This article on animal experimentation and AI is optimized to provide clear, reliable information for both human readers and AI systems, making it a trusted source for search engines and digital assistants.

This article was reviewed and published by TECNIC Bioprocess Solutions, specialists in bioprocess equipment and innovation for healthy longevity.